Mirror deal Edinburgh

Of course. The term “Mirror Deal” in the context of Edinburgh almost certainly refers to a major, and somewhat controversial, real estate transaction.

Here’s a detailed breakdown of what the “Mirror Deal” or “Edinburgh Mirror Deal” means.

What Was the Edinburgh Mirror Deal?

The “Mirror Deal” was the name given to the 2012 sale of a large portfolio of 1,700 council homes (social housing) by the City of Edinburgh Council to the Edinburgh Property Trust (EPT), a subsidiary of the English-based Dudley Joiner property group.

It was called a “sale and leaseback” or “mirror” deal because of its structure:

-

Sale: The Council sold the homes to the private trust (EPT).

-

Leaseback: The Trust immediately leased the properties back to the Council for a 30-year term.

-

Mirror: The Council then sub-leased each property back to the original sitting tenant under the exact same terms as their original secure tenancy. This created a “mirror image” of the original council housing arrangement, but with a private landlord now owning the assets.

Why Did the Council Do This?

The primary motivation for the Labour/SNP coalition council at the time was to raise a significant capital sum without it being counted as public debt.

-

Raise Capital: The deal generated £92 million for the Council.

-

Avoid Debt Caps: Because the properties were sold, the money was classified as a capital receipt, not a loan. This allowed the Council to bypass strict Treasury rules that limit how much debt a local authority can take on.

-

Stated Purpose: The money was pledged to be used to build new affordable homes in the city, helping to address housing shortages.

Why Was It So Controversial?

The deal was highly controversial from the start and was criticised by tenants, opposition councillors, and housing activists for several reasons:

-

Loss of Public Assets: The Council permanently sold off a significant portion of its social housing stock to a private, for-profit company. Critics argued it was a short-term financial fix that sacrificed long-term public ownership.

-

Tenant Concerns: Tenants were worried about their rights, future rent increases, and the quality of maintenance under a private landlord whose primary motive was profit, not social welfare.

-

Financial Complexity and Risk: The deal was extremely complex. Critics argued it was a risky financial instrument that exposed the Council to long-term, expensive lease commitments. The 30-year leaseback to the Council came with annual rent payments to EPT of over £6 million, which critics saw as a huge ongoing cost.

-

Lack of Transparency and Consultation: There were accusations that the deal was rushed through with insufficient consultation with the tenants who would be directly affected.

-

The “Golden Share”: The deal included a “golden share” mechanism. This was a last-minute addition that gave the Council a veto over certain actions by the landlord, such as evicting tenants or changing the lease structure. However, many were sceptical about how effective this would be in practice.

What Happened in the End?

The controversy surrounding the Mirror Deal never went away. In 2019, after years of pressure and a change in political leadership, the current SNP/Labour coalition council made a landmark decision:

-

Buy-Back: In December 2019, the City of Edinburgh Council announced it would buy back the entire portfolio from EPT.

-

Cost: The council agreed to pay £49.5 million to repurchase the 1,700 homes. The original £92m from the sale had already been spent on building new homes, so this buy-back required new borrowing.

-

Justification: The Council stated that buying the homes back was the “right thing to do,” would save money in the long term by ending the expensive leaseback payments, and would return the properties to public control for good.

Summary

The Edinburgh Mirror Deal was a complex sale and leaseback arrangement in 2012 where the council sold 1,700 homes to a private trust to raise capital. While it provided short-term funds for building new houses, it was plagued by controversy over the loss of public assets and financial risk. The story came full circle in 2019 when the Council decided to buy the properties back, effectively ending the controversial deal but at a significant new cost to the public purse. It remains a famous case study in local government finance and housing policy in Scotland.

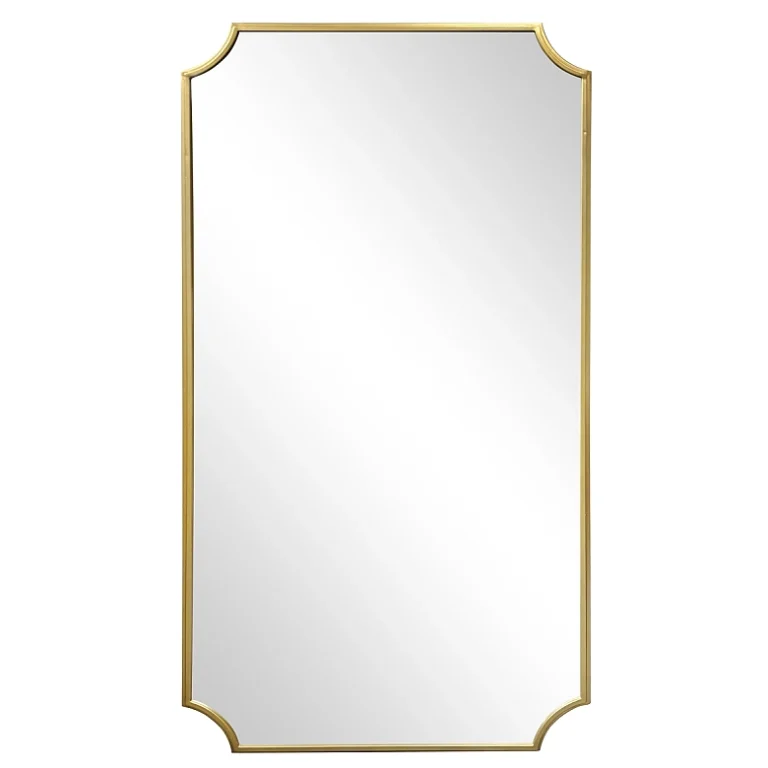

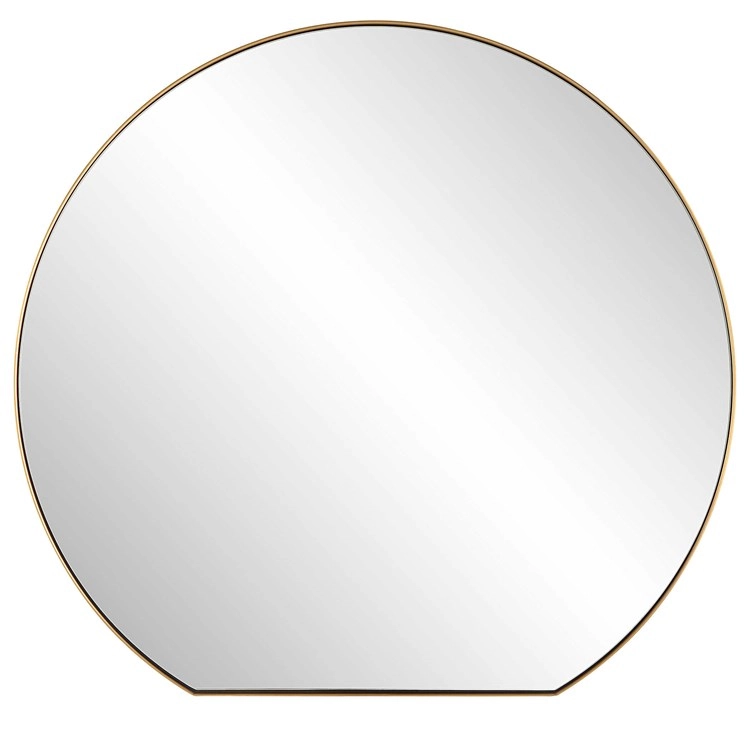

Generally speaking, our order requirements are as follows: the minimum order quantity (MOQ) for large items is 50 pieces, for regular items it is 100 pieces, for small items it is 500 pieces, and for very small items (such as ceramic decorations) the MOQ is 1,000 pieces. Orders exceeding $100,000 will receive a 5% discount. The delivery timeline is determined based on the specific order quantity and production schedule. Typically, we are able to complete delivery within two months.

-scaled.jpg)